Situational Football

Many commentators pointed out that the numbers I used for the case-studies did not account for the wide variety of circumstances in a football game or they simply pointed out their situation by situation method for calling plays, such as hoping to get 4 yards on first down and then splitting the distance on second.

First, I apologize if I was unclear in my last post but I am a big believer in "thin-slicing" football data to get as specific as possible to as many different situations while keeping an eye on sample size. I simply used the broad year-long data to get a ball-park idea and to refer to teams most readers are familiar with. My hope is that any coach who applies the average per play analysis to his team will separate out the data into 1st and 10 between the 40s, red zone, 40 and in, while eliminating huge blowout games, etc.

Each coach will have to use judgment to decide what data is and is not relevant, but I never intended the only calculation to be based off year-long data. I simply assumed that using basic data would be easier for demonstration.

The Case for Average Gain Per Play

The more interesting issue though is why are we using this data at all rather than lower benchmarks like trying to just get 4 yards per play and then ignoring any gain over and above that. My response is two-fold: One, the data bears out that to win games offenses, at least in competitive games before getting a lead, should strive to score points, and second, that teams who get first downs score points, and some basic analysis helps show that teams that average more per play--even when riskier--get more first downs than teams who trade off average gain for risk reduction (i.e. too many running plays).

I'll come back to this again later, but here is a quote from Carolina Panthers Offensive Coordinator Dan Henning (one of the best offensive minds ever, he learned from greats like Sid Gillman and even tutoted Charlie Weis in football offense) that I pulled right from the Carolina Panthers playbook:

Football, in any classification is a percentage game. A Quarterback who goes against percentages too often will fail. He'll have to be extremely lucky. No one figures to be that lucky due to so many extenuating circumstances involved in a 22 man game.

The following rules for play calling have been established for the Panthers to reduce the margin for tactical error. Errors in play calling will kill us quicker than mistakes in any other phase of football.

60% run

40% pass

The above percentage between pass and run is the healthy approach to pro football in any tightly played football game. To run more than 60% of the time will result in low scoring unless we are definitely superior. To pass more than 40% could mean costly losses as the result of failure in pass protection with loss of ball possession and field position due to interceptions.

(Emphasis added) This is very insightful, and what he does not say is instructive. He does not say that you run the ball to be physical, to "establish the run" or we throw to be exciting, or for any reason x, y, or z. All those things might be true, but he simply says that we throw to score points, but it's risky. Running is less risky so we we would run the ball more than 60%, but if we did that we would not score enough points to win.

As we know, the main reason for this is that runs typically do not average as much per play as passes do (unless you've got Reggie Bush). Henning also notes that pass plays have more risk, which I will discuss later in passing premium section.

Thus, we see that the goal is to maximize average gain per play while keeping risk in mind. The risk/return tradeoff in playcalling is one I've thought about quite a bit, most notably regarding the Sharpe ratio here, here, and here.

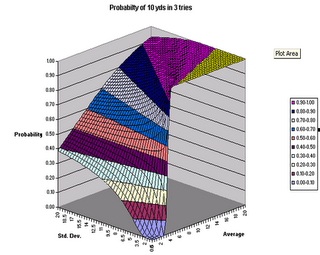

I also posted an article based on a contribution from one of my readers, Brad Eccles. Brad, using a normal distribution, calculated the probability of getting a first down in three plays based on various average or expected gains and standard deviations (where standard deviation is a measure for a play's riskiness, i.e. passes will have gains/losses that can fluctuate from -10 to +20 or more with regularity, while runs tend to be bunched more tightly around their average gain with fewer losses and fewer big gains).

I know this diagram is a bit complicated, but the very steep slope on the right side means that average gain far dominates lower risk when it comes to getting first downs.

The basic gist of this is that in a world without turnovers you would simply try to maximize your average gain per play, and if you could always average more per play by rushing or passing, you would do that (though both rushing and passing have diminishing returns, and at some point you're going to be better off throwing a pass or running even if you hardly ever do it).

In the next section I'll talk about passing's risk per play over rushing, but this is an important conclusion. It implies that if you didn't have to worry about interceptions or turnover risk, then you would not care about run/pass balance at all and you really would just try to maximize your average gain per play whether by running or passing.

(Again, before anyone points out that the rules are different for third downs: I'm well aware, this kind of thinking is mostly for first down and 2nd and 5 and such, which make up the lion's share of all downs actually played. There are only a few third and shorts during a whole season. As I explain in my third Sharpe ratio article, you look at third and fourth downs as success/failure not as gains per play.)

Thus, with the insight that the goal on 1st and (most) 2nd downs should be maximizing average gain per play whether it is from running or passing, I'll turn to the passing premium and turnover risk, or trying to understand how much riskier a pass actually is and how this affects run/pass balance.

The Passing Premium and Turnover Risk

The conclusion that your run/pass mix should be whatever maximizes your average gain per play assumes that runs and passes are equally risky, which of course is not true, as the old adage quoted tells us. But how much riskier are passes, exactly? And what does this say for run/pass balance?

Three things can happen when you pass, and two are bad.

My original run/pass article argued that a football game is a series of Nash Equilibriums: Every down is a little contest and each side must figure out its best strategy using a mixture of runs and passes or different defenses (a "mixed strategy") and should pick the mixture of runs and passes that maximizes (or minimizes, if on defense) average gain per play, subject to the "passing premium," which requires that passes yield more than runs because of their greater risk.

But what is this risk, and how big should the premium be?

Using rough season-long numbers, we saw that Texas Tech and Florida were at about a yard, Southern Cal was a little less, NFL teams average about 2.5 yards, and Minnesota was around 2.25. I argued that Minnesota should have probably passed more, but that was somewhat speculative. To really know we need to better be able to figure out a value for this passing premium. The other problem is it is going to vary team by team, as some teams throw more interceptions than others, etc. Still, the better we understand the risk components the better shot we have.

Again, look at what Henning said:

To run more than 60% of the time will result in low scoring unless we are definitely superior. To pass more than 40% could mean costly losses as the result of failure in pass protection with loss of ball possession and field position due to interceptions.

Henning, at least implicitly, seems to argue that he'd be a lot more comfortable with throwing every down if he never got sacked and never threw interceptions. I think we can go a bit farther and, once we've isolated some of the factors, maybe go back and gather some numbers. I'll label this risk "turnover risk," though it maybe should be called "passing turnover risk minus running turnover risk" as it is the risk of throwing versus running, since the only riskless play has the QB just fall down, and even on that the snap can go wrong.

1. Interception Risk - Per play basis. This article and reader Brad Eccles note that 50 yards per interception could be a decent approximation; so you'd subtract 50 yards from your passing total every time you threw an interception.

2. Fumble Risk - I don't have great data on this, but QBs tend to fumble more than RBs (think about turnover machine Kurt Warner) and receivers are quite vulnerable as well so, a priori, I think there's a greater risk of fumbling on passing plays. [As a coaching point, I always stressed to my QBs to keep both hands on the ball when in the pocket. This makes a huge difference.]

3. Third Down Risk - I think this is the hardest one. As one reader noted, even poor rushing teams are rarely in third and 10, as failed runs usually net at least one or two yards. However, two failed passes in a row (which happens 10-15% of the time even with good passing teams) results in third and 10, which is hard to convert.

For example, if a team has a 65% completion percentage (assuming it stays the same on each down, which I know is somewhat unrealistic), then there is a 12.25% chance that the team will throw two incompletions in a row. If the team has a 55% completion percentage then there is a 20% chance they will wind up in 3rd and 10. This is a very real problem as it can significantly reduce the probability of converting for a first down, as this graph detailing third down efficiency shows:

[Hat tip: MGOBlog]

To properly calculate the risk of failed third downs from a pass attempt on first or second one would have to use the chance of an incompletion along with the reduction in the chance of converting for a first down, and then convert this to a yardage value. I have some ideas how to compute this but I'll save it for another day.

4. Sack Risk - Sack risk has been shown to be somewhat overblown, and its importance depends on down and distance and where the ball is on the field. Still, a sack on third down can (a) see a direct loss of points if it takes one out of field goal range or reduces the chance of converting a field goal, and (b) hurt overall field position, and using some of the analyses that have been done you can hang a point value on the difference between your opponent starting on his 35 and his own 45.

5. Injury Risk - I'm not sure how to quantify this, but in the NFL it might be the dominant reason why the passing premium seems to run higher than in college. Few NFL QBs make it through entire seasons without missing time, and more passes mean more hits which means more injuries. Even if it is not the hits, it could be the chance for injuries from someone rolling over the QB's leg, etc. I do think this of major concern in the NFL, while not as much in High School of College.

6. Uncertainty - I think this is an important one, at times overvalued and other times under valued. While doing some reading several commentators noted that the number of interceptions even NFL QBs threw varied wildly. Also, several teams with high and and seemingly inefficient passing premiums like Texas and Ohio St had QBs who entered the season with question marks about their passing ability. They ended up being more effective and less risky than originally thought (Vince Young lead the nation in pass efficiency) so this could partially explain the outsized passing premium. Compare Brett Favre, whom no one expected to throw 29 interceptions. Green Bay no doubt underestimated turnover risk per pass last season with a future Hall of Famer at QB.

Conclusion

I think these insights are powerful enough to where we can make most, but not all, playcalling decisions with them in mind. As we learn more we can begin approximating or building a model for turnover risk, to more accurately determine what is a sound passing premium per team. Until then, we do know that the most important factors in winning games are turnovers, third down percentage, and average gain per play (and explosive plays and red zone percentage). Taking that into account, on the majority of downs--first and most second downs--coaches should try to maximize their average output, while requiring a high enough passing premium to reward them for the increased risk from throwing the ball.

This is because the data and analysis show that it is average gain, not low standard deviations (like on run plays) that get first downs. However, turnovers and negative plays directly tie into points for the other team. Balance, then is not a matter of how many runs and how many passes, but how good you are at both and making sure you are rewarded for passing's increased risk as this is the way to more first downs, more points, and more wins.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar